The CFO’s Guide to Accounting Memos: Documenting Judgement Calls with Confidence

Every CFO knows the uneasy feeling of making a high-stakes accounting judgement call. Whether it’s deciding when to recognize revenue on a complex contract or how to classify a major acquisition, these decisions can significantly impact financial statements – and stakeholder trust. In an era of increasingly complex standards and recent corporate accounting scandals, finance leaders are under pressure to “get it right” and prove they got it right. This is where robust accounting memos become the CFO’s secret weapon.

Accounting memos are formal written analyses that document the reasoning behind key financial decisions and accounting treatments. Far from mere paperwork, they act as a safeguard for finance leadership by creating a clear audit trail of how and why a judgement was made. In practice, a well-crafted memo instills confidence – for the CFO, for auditors, for the board, and even for future team members – that a subjective accounting decision is backed by thorough research and sound reasoning. This guide will explore why these memos are so critical, what auditors look for in them, and how they help finance teams navigate subjective decisions with clarity. We’ll dive into real-world scenarios (UK FRS 102 and IFRS focused), offer a step-by-step case study, and share best practices. By the end, you’ll see how documenting your judgement calls can turn stressful decision-making into a confident, well-controlled process.

Why Accounting Memos Matter for CFOs

1. Safeguarding Decisions and Building Trust: An accounting memo serves as an insurance policy for your decision-making. It records the key facts, analysis, and conclusion behind a judgement call so that anyone (from auditors to the audit committee) can understand the rationale. In effect, the memo is proof of due diligence. If questions arise months or years later, the CFO can pull out the memo to show exactly how the decision complied with applicable standards and regulations. This kind of documentation boosts transparency and trust with stakeholders. After all, it’s much easier to stand behind a decision when you have a detailed explanation on paper.

2. Aiding Financial Decision-Making: The very act of drafting a memo forces a rigorous thought process. Before a CFO finalizes a judgement, the finance team will research the relevant accounting standards, evaluate alternatives, and articulate their reasoning. This ensures that decisions are not made on gut instinct or flimsy justifications. In fact, memos often illuminate nuances that leadership might otherwise overlook. For example, a CFO might be eager to accelerate revenue growth, but a memo on a new sales incentive program could reveal that extended payment terms would require classifying some revenue as interest under IFRS 15 – undermining that goal. By flagging such issues early, accounting memos inform strategic choices and help “navigate away from unanticipated accounting accidents”. In other words, memos don’t just document decisions after the fact – they improve the quality of those decisions upfront.

3. Clarity in Subjective Areas: Many accounting standards (especially IFRS-based ones) are principles-based, meaning management must apply judgement in areas like revenue recognition, asset valuation, or lease classification. Without documentation, these subjective calls might appear arbitrary to others. An accounting memo translates subjective decisions into a clear narrative: it lays out the company’s interpretation of the principle and how it fits the company’s situation. This clarity is invaluable internally – your finance team, controller, and CFO all align on the “why” behind a treatment. It’s also handy when explaining results to the board or investors. For instance, if you’ve decided to treat a complex financing as equity rather than debt, a memo helps the CFO confidently explain to the board, “Here’s the reasoning and authoritative support behind that position,” rather than just saying “we think it’s right.” Ultimately, memos ensure that subjectivity is backed by substance, giving leadership greater confidence in the numbers reported.

4. Institutional Memory and Continuity: Turnover is a reality in finance teams – CFOs, controllers, and accountants eventually move on. Without written documentation, a company might literally forget why a certain approach was taken. As one audit professional put it, companies should want to maintain technical accounting memos from both a SOX compliance and legal perspective. There’s “nothing like getting questioned on something you did in the past and someone goes, ‘…well, the guy who did that left the company two years ago, so we don’t really know why it was done that way.’ That isn’t going to fly with the lawyers and regulators. In short, a robust memo protects your organization from the “what happens if Bob/Barbara leaves?” problem. It preserves the rationale behind past judgements so that future CFOs and auditors aren’t left guessing. This continuity is also an internal control strength – it demonstrates that management’s significant judgements are well-documented and not dependent on one individual’s memory.

5. Confidence for Boards and Audit Committees: From a management perspective, having thorough accounting memos can turn potentially contentious accounting judgements into non-events. Audit committees and boards take comfort knowing that for every major estimate or policy decision, there’s a paper trail showing management’s thought process. Instead of lengthy debates in audit committee meetings about “did we consider X or Y?”, the memo already outlines all considerations. This not only expedites governance discussions but also enhances the CFO’s credibility. You’re signaling that management proactively addressed complexity and isn’t hiding anything. Especially in high-stress scenarios – say an impairment decision in a downturn – presenting the board with a well-reasoned memo can shift the tone from skepticism to confidence. It provides that extra layer of assurance that the CFO and finance team are on top of the details and compliant with accounting standards.

What Auditors Look for in Technical Memos

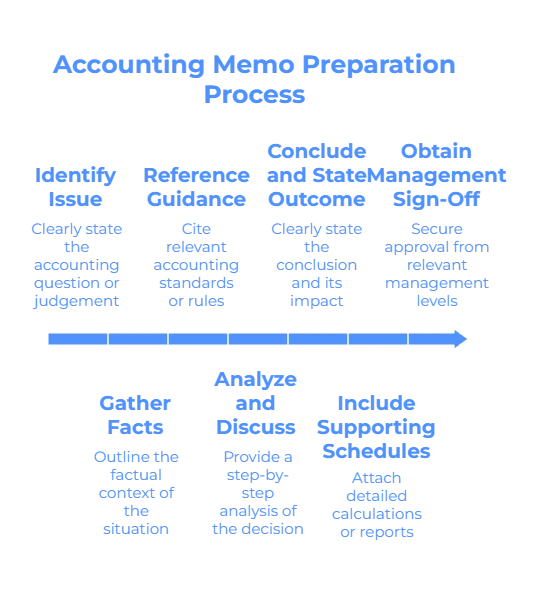

One of the biggest advantages of preparing technical accounting memos is smoother audits. External auditors love a good memo – in fact, they often request client-prepared memos for significant transactions or tricky areas as part of the audit PBC (Provided By Client) list. But what exactly makes a memo “audit-ready”? Let’s break down the key elements that auditors look for:

-

Clear Description of the Issue: A quality memo opens by stating the accounting question or judgement at hand in plain terms. Auditors should immediately see what decision was made (e.g., “determining whether XYZ acquisition constitutes a business combination under IFRS 3” or “revenue recognition method for ABC contract under IFRS 15”). This framing of the issue is crucial – it tells the auditor that management identified a potential risk area and tackled it head-on, rather than glossing over it.

-

Relevant Facts and Background: Auditors expect the memo to outline the factual context – the who, what, when of the transaction or situation. For example, if the memo is about a lease vs. buy decision, it should summarize the contract terms. If it’s about an impairment, it should set the scene of what triggered the review. By including all pertinent facts, the memo spares the auditor from hunting through emails or asking basic questions to understand the scenario. It shows management has a firm grasp of the details underlying the judgement.

-

Reference to Authoritative Guidance: Perhaps the most critical component: explicit references to the accounting standards or rules applied. Auditors want to see that your conclusion is grounded in the appropriate guidance – be it IFRS, UK-adopted IFRS, FRS 102, or even US GAAP if relevant. A strong technical memo will cite the specific paragraphs from standards (e.g., “IFRS 16.B21 defines a lease as… and in this case the criteria are met because…”) and any interpretative guidance (like IFRIC agenda decisions or FRC guidance notes) that influenced the decision. Including these references demonstrates that management did its homework, rather than just guessing. As one CFO advisory firm notes, their technical resources routinely “prepare technical accounting memos for auditor review” as a way to ensure compliance with the latest GAAP/IFRS guidelines.

-

co. In practice, when an auditor sees citations to the literature in your memo, it immediately elevates their comfort – you’ve effectively done part of their audit documentation for them.

-

Analysis and Discussion: This is the heart of the memo – your reasoning. Auditors expect to read a step-by-step analysis of how you arrived at the accounting treatment. This often includes evaluating multiple possibilities. For example, “Management considered treating the transaction as an asset purchase vs. a business combination. We assessed it against the IFRS 3 definition of a business, which requires inputs, processes, and outputs. In our case, we determined that the acquired set does include an organized workforce and processes, thus meeting the definition of a business. Key factors in this judgement were A, B, and C…”. A good memo might also mention alternative outcomes (“Had the acquisition been deemed an asset purchase, we would account for it differently – e.g., no goodwill – but since criteria were met, we will record goodwill of £X”). By showing your work in this manner, you make it easy for the auditor to follow the logic and see that no stone was left unturned. Remember, auditors are trained to approach judgements with professional skepticism; a thorough analysis in the memo pre-empts many skeptical questions because you’ve already asked and answered them yourself.

-

Conclusion and Outcome: After the analysis, the memo should clearly state the conclusion – essentially, “Therefore, we will account for X as Y.” Auditors look for an unambiguous conclusion that they can tie back to the financial statements. For instance, “Conclusion: The contract contains a lease under IFRS 16, so we have capitalized a right-of-use asset of £Z on the balance sheet.” The conclusion section might also reiterate any quantitative impact (e.g., amounts recorded, any changes made). A pro-tip here is to align the wording of the conclusion with what ends up in your financial statements or disclosures. That makes it even easier for auditors to cross-reference your memo with the draft accounts.

-

Supporting Schedules or Calculations: If the judgement involves numbers – say, an impairment calculation, an effective interest rate calculation for a loan, or an allocation of a purchase price – auditors will expect to see the detailed workings either embedded in the memo or attached as schedules. Referencing these in the memo (e.g., “…see Appendix A for the DCF model supporting the impairment test”) is wise. It shows that the memo isn’t just theoretical but has been taken through to the actual computation and entries. Many finance teams include attachments like spreadsheet printouts, valuation reports, or even external expert opinions as part of the memo package. This comprehensive approach signals to the auditor that all evidence is gathered and organized.

-

Management Sign-Off: Finally, auditors take comfort in seeing that the right level of management has reviewed and approved the memo. A best practice is to have a sign-off or at least an indication of who prepared and who reviewed it (for example, prepared by the Group Accounting Manager, reviewed by the Financial Controller, approved by the CFO). This hierarchy of review tells the auditors the issue got appropriate attention. It also aligns with internal control expectations – for SOX-compliant companies, having formal sign-offs on key judgements is often part of the control process. Essentially, the memo serves as documentation that management has taken responsibility for the judgement (not the auditors). As one auditor on a discussion forum succinctly noted, “The memo shows the client evaluated the guidance and came to the accounting decision. The auditor is reviewing the client’s work, not doing the work themselves.” In other words, a client-prepared memo makes it crystal clear that management owns the accounting positions – which is exactly what auditors (and regulators) expect to see.

How does all this benefit the audit? Simply put, it can reduce the back-and-forth. Instead of peppering your team with dozens of questions, the auditors can often tick off the issue in their workpapers by placing your memo in the file and commenting “accounting treatment documented by management – reviewed and in line with GAAP/IFRS.” Issues that might have led to protracted debates can turn into a short discussion, because the heavy lifting (research and rationale) is already done. Additionally, having robust memos may shorten the audit timeline or reduce the risk of an audit adjustment. Auditors, being human, are less likely to second-guess a well-supported position that’s laid out logically. On the flip side, if no memo exists for a significant judgement, expect your audit team to ask a lot more questions and perhaps dig in deeper – after all, lack of documentation is a red flag in auditing. It’s no surprise that many companies engage technical accounting advisors (often ex-Big Four professionals) to help draft memos “the way auditors like to see them”. It’s a worthwhile investment in making the audit process efficient and avoiding unpleasant surprises.

Scenario Examples: When Do You Need an Accounting Memo?

Accounting memos are not needed for every little transaction. They tend to be reserved for areas that involve significant judgement, estimation, or complexity – the kinds of issues that auditors, regulators, or your board are likely to focus on. Under both UK GAAP (FRS 102) and IFRS, typical trigger points for a technical memo include new or complex standards, one-off transactions, or grey areas in accounting literature. Below is a non-exhaustive list of common scenarios where a robust memo can be a lifesaver, along with the key judgement involved and how the memo provides value:

| Scenario (Standard) | Key Judgement Call | How an Accounting Memo Helps |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Element Revenue Contract IFRS 15 (Revenue) – A software sale bundling licenses, support, and customization services. |

Determining distinct performance obligations and timing of revenue recognition (e.g. upfront vs over time). | Documents management’s analysis of IFRS 15 criteria (and FRS 102 Section 23 in UK GAAP) for separating deliverables. The memo clearly justifies when revenue is recognized for each element, providing auditors a step-by-step rationale and ensuring no surprises in how revenue is recorded. It also evidences that the company considered the latest guidance on complex revenue arrangements, which boosts confidence in the reported topline. |

| Lease or Service Arrangement? IFRS 16 / FRS 102 Leases – An outsourcing contract for equipment where the supplier controls the assets. |

Assessing whether the contract contains a lease (right-of-use asset) or is purely a service contract (expense as you go). | Lays out how management evaluated the contract against IFRS 16’s definition of a lease (an identified asset that the customer controls the use of). The memo might walk through each criterion – asset identification, right to obtain economic benefits, right to direct use – and conclude, for example, that “yes, this is a lease” to be capitalized. By documenting this, the memo prevents misclassification that could impact debt ratios and ensures both CFO and auditors agree on the treatment early. |

| Acquisition Accounting IFRS 3 (Business Combinations) – Buying a division or group of assets from another company. |

Deciding if the purchase is a business combination (with goodwill, deferred taxes, etc.) or an asset acquisition (treated differently). | Outlines the facts of what was acquired and applies the IFRS 3 business definition test (inputs, processes, outputs). For example, the memo might note that along with assets, a workforce and processes were acquired, indicating a business. It would then document the resulting accounting (recognition of goodwill, acquisition costs expensed or capitalized appropriately). This gives stakeholders and auditors confidence that the complex rules of acquisition accounting were carefully navigated. The memo can also highlight implications (like goodwill of £X recognized), linking the analysis to financial statement impacts. |

| Goodwill Impairment Review IAS 36 / FRS 102 – Annual test for a cash-generating unit that has shown some decline in performance. |

Whether goodwill (or other indefinite-life assets) is impaired, and if so, by what amount. | Captures the entire impairment testing process: assumptions used in cash flow forecasts, the discount rate, growth rates, and any sensitivity analysis (e.g., “what if revenue was 10% lower?”). The memo explains why management believes the recoverable amount exceeds carrying value (or not). Including workpapers of the DCF model or valuation adds credibility. By documenting this thoroughly, the memo demonstrates that management has been prudent and forward-looking in assessing asset values – a key area of auditor and board scrutiny, especially in tough economic times. |

| Financial Instrument Classification IFRS 9 / FRS 102 – Issuing a convertible loan note to investors. |

Determining how to classify and measure a complex financial instrument (debt, equity, or a bit of both?). | Details the analysis under IFRS 9 (and relevant FRS 102 sections) of the note’s features: interest rate, conversion option, maturity, etc. The memo might conclude that the instrument is a compound financial instrument requiring split accounting (part liability, part equity), and show the calculation of that split. By laying this out, the memo not only supports the journal entries but also helps the CFO explain the impact on gearing and shareholder equity. Auditors will be looking for exactly this kind of documentation given the complexity of financial instruments – it shows the company didn’t wing it. |

As the table above illustrates, any time an accounting decision isn’t black-and-white, a memo is advisable. In fact, IFRS and UK accounting standards explicitly require disclosure of significant judgements in the financial statements (for instance, IAS 1 requires notes on judgements that have the most significant effect on the accounts. Behind each such disclosure typically lies a memo that fleshes out the details.

From revenue tricks to lease traps, accounting memos are your safety net. Consider the alternative: without a memo, an auditor might come back with a list of findings or proposed adjustments on these issues. Many companies have learned this the hard way. Errors in complex areas have led to restatements, audit delays, even enforcement actions by regulators. (For example, revenue recognition errors and lease missteps have triggered costly restatements and audit deficiencies in the past) It’s far better (and cheaper!) to invest the time upfront in a memo that prevents such issues.

Let’s bring this to life with a concrete example of how a CFO and team would actually produce an accounting memo for a tricky scenario.

Case Study: Step-by-Step Memo for a Complex Judgement Call

Scenario: XYZ Ltd, a UK-based company, is acquiring a portfolio of assets and operations from a competitor. The CFO’s team must decide if this transaction is a Business Combination under IFRS 3 / FRS 102, or merely an asset purchase. The distinction is critical: if it’s a business combination, XYZ will record goodwill and acquisition-related costs will be expensed; if it’s just assets, no goodwill is recognized and transaction costs can be capitalized with the assets. The treatment will affect XYZ’s financial statements and key metrics, so it’s a high-stakes judgement call. Here’s how the CFO and finance team tackle it in a series of steps:

-

Step 1: Identify the Issue and Stakeholders – The Group Controller flags early on that “we need to determine what we’re actually buying – a business or a collection of assets”. The CFO recognizes this as a significant accounting issue and ensures the audit partner and audit committee are aware that management will document the conclusion. The stakeholders here include the finance team (who will do the analysis), the CFO (who must sign off), the auditors, and the board. All have a vested interest in getting this right.

-

Step 2: Gather Facts and Context – The deal team provides all relevant information about the acquisition. This includes the contract, term sheet, a list of assets being acquired (equipment, inventory, IP intangibles), and confirmation of whether employees will transfer to XYZ. Let’s say in our case: XYZ is acquiring a production facility with all its machinery, the employees running that facility, and the customer contracts associated with it. Essentially, it’s an operational branch of the seller. These facts are documented at the start of the memo draft to set the stage. The memo lists: assets acquired, number of employees, any processes or systems included, and any outputs (products or revenue) that will continue. This factual baseline will be crucial for the analysis.

-

Step 3: Research the Accounting Standards – The team pulls out the relevant guidance: IFRS 3 Business Combinations (as adopted in UK IFRS) and the equivalent section in FRS 102 (Section 19). The key question is what constitutes a “business”. IFRS 3’s definition (essentially, a business = inputs + processes capable of creating outputs) is noted. The team also checks if there have been updates or clarifications – e.g., the IASB issued an amendment in 2018 about a simplified assessment (“concentration test”) for business vs asset. All this is noted. If available, they might consult high-level summaries from Big Four manuals or FRC guidance for additional clarity. By the end of this step, the team has a checklist of criteria that need to be evaluated against our scenario. They also note the accounting impact of each conclusion (e.g., write down: “If business: will record goodwill = purchase price – fair value net assets. If assets: allocate price across assets, no goodwill.”).

-

Step 4: Analyze and Document the Judgement – Now the heavy lifting: the finance team evaluates XYZ’s acquisition against IFRS 3’s criteria. In the memo’s analysis section, they go criterion by criterion. For instance:

-

Inputs: Yes, XYZ is acquiring inputs – the facility, machines, inventory (raw materials).

-

Processes: Yes, there is an organized workforce and established processes to manufacture goods. The memo might quote, “The acquired set includes an operational management team and standard operating procedures for production – thus meeting the ‘processes’ element.”

-

Outputs: Yes, there are outputs – the facility produces goods that generate revenue (and XYZ will take over fulfilling customer contracts).

Given these points, the analysis leans toward “this is a business”. The team also applies the optional “concentration test” (if substantially all the value is in one asset or group of assets, it might indicate not a business). In our case, value is split between inventory, PPE, and goodwill expectation – not concentrated in a single asset – further supporting business treatment.

The memo then explicitly states something like: “Based on the criteria, management’s judgement is that the acquired set constitutes a business as it includes necessary inputs and substantive processes capable of generating outputs.” To bolster this, the memo references IFRS 3.B7 which provides examples, and perhaps notes “this situation is analogous to Example 1 in IFRS 3 Illustrative Examples, which was deemed a business.” The analysis might also discuss any close calls – e.g., “Had no employees or processes transferred, the conclusion might differ, but in this case they did.”

Finally, the team quantifies the accounting: they list the fair values of identifiable assets (from valuation reports) and determine the goodwill that would arise. Suppose purchase price is £50m, identifiable net assets are £40m, then goodwill of £10m will be recorded. They also note that transaction costs (say £1m of legal fees) will be expensed in P&L, per IFRS 3. Conversely, the memo briefly states, “If this were an asset purchase, no goodwill would be recorded; instead asset values would increase and transaction costs capitalize – but that scenario does not apply given our conclusion.”

-

-

Step 5: Review and CFO Sign-Off – The draft memo is circulated internally. A senior technical accountant or an external advisor reviews it to ensure it’s rigorous and that all necessary references are included. The CFO then reviews the memo with the finance team, asking probing questions (“Are we sure no intangible asset could account for the purchase price difference instead of goodwill?”, “Did we consider deferred tax implications?” etc.). Satisfied with the answers and perhaps after a round of refinements, the CFO formally approves the memo. The final document is signed by the CFO and the Group Controller.

-

Step 6: Communicate and Archive – The conclusion from the memo is now incorporated into XYZ’s accounting records. Goodwill is booked, and disclosures for the business combination (per IFRS 3 / FRS 102) are drafted using the memo as a source. The CFO uses the memo’s findings to brief the CEO and the board: “We determined that the acquisition is a business combination, which means we’ll record approximately £10 million of goodwill. We’ve documented all of this thoroughly.” The auditors, who were informed of this process from the start, receive the finalized memo and quickly review it. Thanks to the memo, the audit work on this area is straightforward – they primarily verify the numbers and check that the memo’s logic holds up (which it does). The memo is saved in the company’s central accounting policy library, to serve as a precedent for future deals. XYZ can also leverage it if the Financial Reporting Council (the UK regulator) ever questions this treatment during a review – they’ll have a comprehensive justification on file.

This step-by-step case demonstrates how an initially daunting question (“Is this a business or not?”) gets methodically resolved through a memo. The CFO can now sleep at night knowing that if anyone challenges the accounting, the answer is “We have a 10-page memo on that – would you like to see it?” 😊 (Notice we maintained a slightly relaxed, conversational tone here – because documentation doesn’t have to be dry!). In all seriousness, the CFO in this scenario turned a judgement call into a well-supported decision, thanks to the memo process. And importantly, the company’s financial reporting is both accurate and defensible.

International Perspectives: Memos in a Global Context

In today’s global business environment, CFOs often grapple with multiple accounting frameworks. A UK CFO might oversee IFRS reporting for consolidation, while some subsidiaries report under local standards (be it UK FRS 102, US GAAP, or others). The good news is that the concept of robust accounting memos transcends accounting regimes – it’s a universally recognized best practice for sound financial governance.

-

IFRS vs. US GAAP: IFRS (used by UK-adopted IFRS reporters and many global companies) is principles-based, requiring management judgement in areas like revenue recognition, leases, and consolidation. U.S. GAAP, on the other hand, can be more rules-based but still contains plenty of complex areas (just think of the detailed rules for derivatives or lease classifications under ASC 842). In both frameworks, auditors and regulators expect to see documentation of significant judgements. A memo on an IFRS 15 revenue question will look quite similar in spirit to a memo on the equivalent ASC 606 issue – both will cite the standard, lay out assumptions, and justify the timing of revenue. The internal control environment under SOX in the US has actually made such memos practically mandatory for public companies. Many U.S. CFOs ensure that for any complex transaction, a formal memo is prepared as part of their SOX 404 key controls (often, a control might literally be “Controller’s team documents accounting treatment for non-routine transactions and reviews with CFO”). In Europe and the UK, while it may not be a legal requirement to the same extent, the practice is equally valued for audit defense. In fact, global audit firms often deploy the same methodology worldwide: if it’s a judgement call, write a memo – otherwise face a potential audit finding.

-

Cross-Border Transactions: International operations introduce scenarios where memos can be crucial to ensure consistency. Imagine a situation where a UK parent company (IFRS) has a US subsidiary (reporting in US GAAP) and enters a complex intercompany arrangement or group restructure. The accounting teams might need to reconcile differences between US GAAP and IFRS treatments. Here, preparing a memo that outlines how the transaction is accounted for under each GAAP, and any consolidation adjustments needed, will save headaches. It creates a common reference for auditors in both jurisdictions. Furthermore, if translations to local statutory GAAP are required (say converting an IFRS result to local China GAAP or India GAAP for filings), memos can document those adjustments in a structured way. Essentially, memos become the ** lingua franca ** for the finance organization – a consistent format to discuss accounting issues, no matter the country or standards involved.

-

Local GAAP (FRS 102) vs. IFRS considerations: For UK companies specifically, many mid-sized firms report under FRS 102 (the UK GAAP for entities not using full IFRS). FRS 102 has historically been simpler than IFRS in some areas, but it’s evolving – recent amendments are aligning revenue recognition and lease accounting in FRS 102 more closely with IFRS 15 and IFRS 16. Regardless, when applying FRS 102, judgement calls still abound – for example, deciding the useful life of goodwill (since FRS 102 requires amortization, unlike IFRS) or determining if a financing arrangement has an embedded derivative. Here too, memos are gold. They provide a space to explain, say, why management chose a 5-year amortization for goodwill (perhaps based on certain industry patterns), or how a hybrid instrument was split between liability and equity under FRS 102’s Section 11/12. One could argue that because FRS 102 is less detailed than IFRS in some respects, documenting your interpretations via memos is even more important – you might be filling in gaps with judgement. Additionally, if a company ever transitions from FRS 102 to full IFRS (for example, on the path to an IPO), having memos on key accounting positions can ease the conversion process, as they highlight where differences might lie.

-

Regulatory and Cultural Expectations: Different countries’ audit cultures have varying expectations on documentation. Anglo-Saxon markets (UK, US, Canada, Australia) are generally documentation-heavy – the mantra is “if it’s not documented, it didn’t happen.” In contrast, some smaller markets might historically have been more conversation-based. But the trend globally is towards more written documentation, not less. With increasing scrutiny on audits and financial reporting (e.g., PCAOB inspections in the US, the FRC’s audit quality reviews in the UK, etc.), audit firms are themselves being pushed to demand better evidence from clients. In practical terms, that means even if you’re a CFO in, say, an emerging market that adopted IFRS, your auditors (especially if they are part of a global network) will likely encourage the use of memos just as if you were in London or New York. In multinational organizations, group finance can set a tone by requiring all local units to document certain types of issues in a memo to be shared with HQ. This not only harmonizes accounting treatments but also helps identify if a local team might be struggling with an interpretation – HQ can catch it and assist, using the memo drafts as insight.

Bottom line: Wherever you operate, robust documentation is a universal best practice. It transcends language barriers too – a well-structured memo with references and conclusions is something an auditor in any country can follow. For the CFO, this means peace of mind that no matter where a judgement is made in your organization, it’s being handled with the same care and diligence. And if you ever need to justify your accounting to an overseas regulator or align two sets of books, you have the memos to back you up.

Best Practices for Writing Effective Accounting Memos

By now, we’ve established why you should create accounting memos. Now let’s talk about how to do it right. A memo is only as good as its content and clarity. Here are some tips and best practices to ensure your memos hit the mark:

-

Use a Clear and Logical Structure: Follow a standard format so that readers know where to find what they need. A tried-and-true structure includes: Purpose/Issue, Background, Analysis, Conclusion, and Recommendations/Actions. Start with a short intro stating the purpose (e.g., “to document the accounting treatment of XYZ under IFRS”). Provide background facts as needed (but avoid unnecessary history). Then lay out the analysis with headings and even sub-headings if the issue has multiple parts. Finally, conclude and state any next steps (like “no further action needed” or “will monitor X assumption going forward”). Also list attachments at the end if you have them. Consistency in format makes it easier for others to digest. As one guide notes, having standard sections like introduction, background, body, conclusion, and attachments helps organize information logically for the reader.

-

Be Concise yet Complete: Aim for that sweet spot where the memo is thorough but not an encyclopedia. Use clear, straightforward language – you’re not writing a novel or an academic thesis. If a memo starts turning into a 30-page monster, consider if some detail can be moved to appendices or referenced documents. The goal is that a reasonably informed reader (say your Audit Committee chair or a new controller) can read the memo and grasp the issue without drowning in minutiae. That said, don’t skip over critical details or assumptions just to save space. Every assumption that feeds the judgement (like “we assume a 5% discount rate based on X”) should be mentioned. The key is to write in a tight, focused manner. Bullet points or tables can help break up dense text and convey information efficiently (for example, summarizing key terms of a contract in a bullet list). Remember, clarity trumps cleverness – avoid jargon if plain English will do, and explain any technical terms that are unavoidable. If the memo is going to be shared beyond the accounting team, it’s even more important to keep the language accessible.

-

Ground Statements in Evidence: This is about credibility. Whenever you make a statement in the memo, consider backing it up either with a reference or with data. If you say “this treatment is in accordance with IAS 38,” cite the paragraph of IAS 38 or a guidance excerpt. If you conclude “no impairment is needed,” reference the calculated headroom from your model (e.g., “headroom of £2.5m, see Appendix for calculation”). By tying statements to evidence, you make the memo audit-proof. It leaves little room for someone to challenge, because you’ve shown exactly where it comes from. Providing references isn’t just for external readers – it also helps your internal reviewers double-check the work. As a plus, if you (or someone else) revisit the memo in a year, those references will point them to the source material immediately. This evidence-based approach echoes a common tip: provide references within your memo rather than just assertions.

-

Consider Your Audience: Tailor the depth and tone of the memo to who will read it. A highly technical memo intended only for the auditor and technical accounting team can be detailed and use accounting lingo freely (they’ll understand terms like “component depreciation” or “IFRIC agenda decision”). But if the memo might be shared with non-accountants (say the CEO or operational management), include brief explanations for technical terms or implications. For instance, you might add a sentence like “(In simple terms, this means….)” to translate a complex concept. Maintaining a professional tone is important – memos are formal documents – but you can still be approachable in style. Avoid overly legalistic language or unnecessary passive voice. Write it almost like you’re explaining to a colleague in conversation, but with a structured flow. And definitely avoid emotional or opinionated language (don’t say “we feel this rule is ridiculous” – even if you think so!). Stick to facts and reasoned judgement.

-

Include Alternative Views (if relevant): A strong memo can sometimes acknowledge other approaches and why they were not taken. This is not mandatory for every memo, but in contentious areas it’s a savvy move. For example, “Management considered classifying this instrument as equity. However, because it includes a mandatory redemption feature, it fails equity criteria under IAS 32 – hence liability classification was chosen.” By documenting this, you pre-empt the question “why not treat it another way?” that an auditor or reader might ask. It shows you’ve done a 360-degree evaluation. Just be careful: if you mention an alternative, be sure to clearly state why it was rejected to avoid any doubt about your final conclusion.

-

Use Visual Aids Where Helpful: Sometimes a table, flowchart, or diagram can explain something better than text. Don’t shy away from inserting a simple table of numbers (e.g., reconciliation of lease payments vs. lease liability) or a decision tree (Big 4 guides often have decision flowcharts for leases, revenue, etc. – you can adapt those). Visual elements can break the monotony of a text memo and drive home key points. For instance, in a memo about segment reporting, a small org chart graphic showing which entities fall into which segment can help the reader follow along. Just remember to keep visuals clear and label them (e.g., “Table 1: Summary of Cash Flows used in Impairment Test”). The goal is to enhance understanding – so if a visual doesn’t add new info or clarity, it may not be needed.

-

Review and Proofread: Treat an accounting memo with the same respect you would a published financial report. Typos, calculation errors, or unclear sentences can undermine the memo’s credibility. Always have a second pair of eyes review the memo. Often a colleague or someone not deeply involved in the issue can spot if any logic leap doesn’t quite follow. They might say, “I don’t understand how you went from point A to point B here,” which is invaluable feedback – because if they don’t get it, likely an auditor might not either. Also ensure consistency – if you cited “IAS 1.123” somewhere, double-check it’s the correct paragraph; if you stated a fact in background, ensure the same fact is used in analysis (e.g., don’t list one purchase price in background and a different one in conclusion by accident!). A final proofread for grammar and formatting will polish it up. Remember, this memo might live on as a workpaper for years; you want it to reflect well on the finance team’s professionalism.

-

Keep Memos Accessible: A practical point – store your accounting memos in a well-organized repository. Whether it’s a shared drive, a documentation software, or an accounting memo binder (if you’re old school), make sure they’re easy to find for those who need them. Consider indexing them by topic and date. There’s nothing more frustrating than knowing you wrote a great memo and then scrambling to find it when the auditor asks a year later. Also, as time passes, periodically review if older memos need updating (e.g., if a new standard or new facts come into play, you might add an addendum or a follow-up memo). An outdated memo is still better than none, but you should note changes when they occur.

By following these practices, you’ll produce memos that not only satisfy auditors, but also serve as an internal knowledge base for your team. In fact, robust documentation habits can be contagious – other departments (like tax or legal) might start emulating it for their analyses too, once they see the finance team’s memos. It all contributes to a culture of diligence and clarity.

Conclusion: From Judgement Calls to Confident Conclusions

In the fast-paced world of finance, CFOs and finance leaders are constantly called upon to exercise professional judgement. The difference between a decision that keeps you up at night and one you confidently stand behind often comes down to how well it’s documented and reasoned. Accounting memos transform those “close-call” decisions from potential vulnerabilities into sources of strength. They act as your safety net, your communication tool, and your defense dossier all in one. When done right, an accounting memo says to any reader – be it an auditor, a board member, or a regulator – “We’ve done our due diligence, here’s the evidence.” That builds trust and credibility, both in you as a finance leader and in the financial reports your team produces.

From safeguarding leadership and aiding decision-making, to satisfying auditors and educating stakeholders, the humble memo punches far above its weight. It brings discipline to subjective areas and ensures that even when accounting feels like an art, there’s a solid canvas of analysis behind it. As we saw in the scenarios and case study, companies of all sizes – whether reporting under UK FRS 102 or international IFRS – stand to gain from embracing this practice. It’s no wonder that organizations with strong technical accounting documentation tend to navigate audits and regulatory scrutiny more smoothly, often saving time and cost in the long run.

For CFOs, investing in a robust memo process is an investment in peace of mind. It’s about creating a legacy of sound decisions that future finance teams can learn from and build upon. And you don’t have to do it alone. Many finance teams leverage experienced accounting advisors (like our team of ACA-qualified, ex-Big Four professionals) to review or even prepare technical memos, ensuring they meet the highest standards of quality and thoroughness. Bringing in an external perspective can be especially valuable for very complex or novel transactions – we can help benchmark against how others documented similar issues and make sure nothing is missed.

If reading this has sparked thoughts about your own accounting judgements and whether they’re adequately documented, it might be a good time to take action. We’re passionate about helping companies strengthen their financial reporting through better documentation and controls. Interested in making your accounting memos (and judgement calls) more robust? We invite you to reach out and book a discovery call with us. It’s an informal, no-obligation chat where we can discuss your specific challenges – whether you’re grappling with an IFRS conversion, a tricky consolidation question, or upcoming audit prep – and see how our expertise in technical accounting and memo preparation can help. Often, just talking through the approach to a memo can clarify the accounting itself!

Lastly, as a gesture to help you get started, we’ve put together a handy PDF guide/checklist on crafting effective accounting memos – covering key sections to include, common pitfalls to avoid, and a template structure. Feel free to request this free resource during your discovery call or via our website. Think of it as a cheat-sheet to reinforce the best practices we discussed here.

In summary, accounting memos might not grab headlines, but they are the unsung heroes of financial reporting. They let CFOs document judgement calls with confidence – turning judgement into justified action. So the next time you encounter a thorny accounting question, don’t just make the call… memorialize it in a memo. Your future self (and your auditors) will thank you!